This is an abstract of the talk I did at the Indie Gameleon festival on September 15, 2015; supplemented by material from a lecture I give to students.

When you’re building your game, of course you’re going to want to have a story included, right? You know how much people love game stories – not to mention all the memorable stories you personally enjoyed in your favourite game. So let’s add some story to your game!

Actually, let’s not.

You might not expect to hear this coming from a guy who writes stories for games, but I don’t want developers to blindly implement stories in their games. What I desire, is that we produce smarter stories, not more.

Sadly, there is no magical formula that creates a brilliant story that will enhance your game by default. There is no equation of

[Protagonist + Conflict + Resolution = Great Story = Profit]

Instead, I think a game development team needs to ask themselves critical questions before recklessly adding just any story to their game. Game Design is about making deliberate choices, and I am under the impression that stories are often thrown into the development process without much thought. I think we can remedy this practice by being mindful of a few principles and ideas.

I distinguish four functions a story can play in your game. Most games feature overlapping functions, and that’s all right. A story can have more than one function, as long as you understand why.

Explanation (or Excuse)

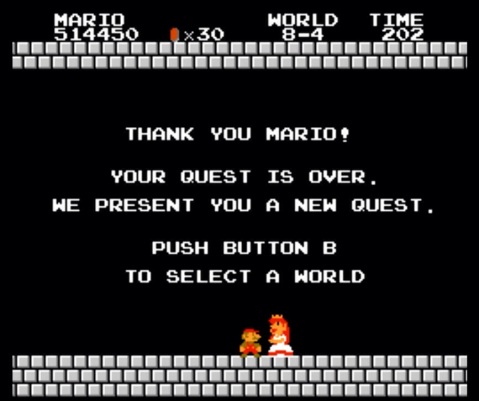

Sometimes, your game just needs an explanation to tie all the different parts and design choices together.

The story in this case provides a setting, which pretty much acts as a flavour. This function is found in a wide range of titles, especially classic titles. There is no apparent link between the story and the gameplay; the story only functions for the player to roughly understand why he is jumping on mushroom men, why he is mowing through waves of zombies, or why he is slinging suicidal birds at green pigs.

Often, the story is used to accentuate a unique gameplay mechanic or art style direction, while at the same time excusing it. This is especially true for the ‘save the princess’-trope associated with a lot of games. You can use a cheap objective like saving a princess, winning a championship, or defeating a big bad bully to excuse your gameplay – often in a wacky way.

It is entirely possible that there is more to the story than merely adding a setting to the game. Sometimes it merely provides an illusion of depth. In other cases it originally functioned as an explanation, but adopted a more elaborate function as a series progresses. And let’s not forget: it is perfectly fine for a game to have a story that only serves to explain why you’re doing what you’re doing in the game. There is no value or judgement added to these functions. So if you just want to match your unique game mechanics with a funny or otherwise interesting setting, don’t forget that this could be all you need. There’s no need to create an expansive (background) story just because.

Notable examples:

- Angry Birds series (Rovio Entertainment, 2009)

- Castle Crashers (The Behemoth, 2008)

- Candy Crush Saga (King, 2012)

- Gauntlet (Atari Games, 1985)

- Super Mario Bros (Nintendo R&D4, 1985)

- Super Meat Boy (Team Meat, 2010)

- The Flock (Vogelsap, 2015)

- Wolfenstein 3D (id Software, 1992)

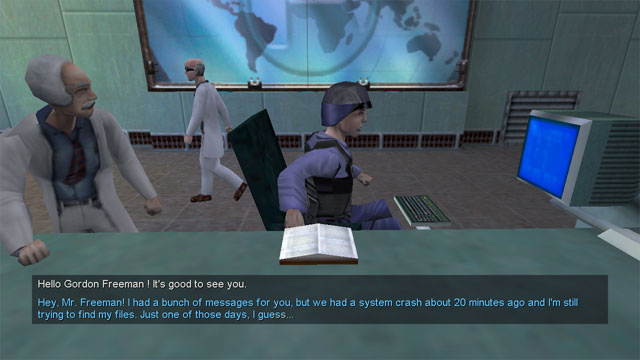

Reward

A story can be used as a reward for the player. He will continue to play because he wants to know how the story ends. This demands that the player is enthralling enough for the player to want to find out how it ends. A lot of the stories in this category are aimed to entertain or evoke some emotion.

For example: Half-Life was the first FPS to feature a story with a meaningful progression and ending. Shooters before that (Doom, Quake, Wolfenstein), all had Explanation-Stories (shoot the demons/aliens/nazis and finally their boss), but Half-Life was the first that made you wonder what would happen to the player character and the world.

The Reward-function appeals to the curiosity of the player. If you can get a player to lose himself in the story, he will return to playing the game until it’s finished. This also works for different endings: when the player has finished one ending, he might be curious enough to want to find out what the other ending are. He seeks the reward of the alternate endings, which compels him to keep playing your game.

Reward-stories are usually heavily designed. They require a strong author to warrant an engaging experience, whether there is one ending or multiple. A worst-case scenario for game stories with the reward-function is an anti-climax: the curiosity of the player – and the time investment that accompanies his curiosity – is either rewarded by a weak, disappointing ending, or there are too many questions left unanswered. Great stories in this category leave the player satisfied and may even leave enough room for curiosity for a sequel.

Notable examples:

- Assassin’s Creed series (Ubisoft Montreal, 2007 and onwards)

- Batman: Arkham series (Rocksteady Studios, 2009)

- Half-Life series (Valve L.L.C., 1998 and onwards)

- Life is Strange (Dontnod Entertainment, 2015)

- Spec Ops: The Line (Yager Development, 2012

- The Last of Us (Naughty Dog, 2013)

- The Walking Dead series (TellTale, 2012)

- The Witcher series (CD Projekt RED, 2007 and onwards)

Make a Statement

You can use a story to really drive your point home. When you feel strong about an issue, or when you want to share a personal experience, then the story in your game will function to send your audience a message. This could also be an artistic statement. Flemish developer Happy Volcano made Winter, in which you build up to a final moment where you decide whether your protagonist, who is at death’s door, chooses to live on, or embraces death. I can’t imagine anyone would gain pleasure, or perhaps even empathy from a story such as that. But at the very least, it’s an attempt to tread on the borders of game storytelling, and I interpret it as a critical comment on the player’s agency (I boldly state, without having ever played the game – correct me if I’m wrong!).

Another example I like to use here is That Dragon, Cancer, developed by Numinous Games. This game deals with the terminal illness of a toddler, inspired by a true story. By making this experience a game, they utilise the player’s agency to put him in the middle of the experience, rather than being an outsider. This results in a higher chance of empathy, instead of just sympathy. But the game stories in this category can have a broader message as well: how society treats homosexuals; how racism is prevalent in society; how cooperations function.

The player is usually served a finely-designed experience that really shows the core of the issue. The message is formulated very clearly in these cases. Alternatively, the player might find himself in the position of the wrong-doer, and might need to realise the results of his actions independently. This requires more critical and reflective thinking of the player, but when this realisation finally comes, it will be al the more powerful (“I’ve been causing pain and suffering all along!”).

Notable examples:

- Braid (Number None. Inc., 2008)

- Deus Ex: Human Revolution (Eidos Montreal, 2011)

- Gone Home (Fullbright, 2013)

- Papers, Please (3909, 2013)

- That Dragon, Cancer (Numinous Games, 2016)

- This War of Mine (11 bit studios, 2014)

- To The Moon (Freebird Games, 2011)

- Valiant Hearts: The Great War (Ubisoft Montpellier, 2014)

Part of Gameplay

This one is trickier and requires some effort from not only a narrative designer/game writer, but from the team as a whole. The story here is not something that is simply presented to the player in bite-sized chunks. No, the player needs to actively look for story here. I’m inclined to distinguish two subcategories in this function: story-puzzles and emergent narratives. “But Gerben, why not make them two different categories altogether? Why are you installing two subcategories under the common denominator of ‘Part of Gameplay’?”

I’m glad you asked! See, although both subcategories lie at opposite ends of the designed-generated spectrum, both require the player to piece a story together – and function the same. So the acts associated with the interpretations are the same, but in one case the story has a defined structure designed by the developers, while in the other case the story elements are up to the player. Allow me to elaborate.

Story-puzzles are fragmented (background) stories that may or not be conclusive in their interpretation, and that may or may not be complete. The player is tasked with looking for story clues, after which these need to be assembled into a coherent whole. The challenge here (or win-condition) is when you finally find sufficient pieces of the puzzle to be able to find out the plot. Players may experience a heightened sense of satisfaction if they are able to solve the story-puzzle ‘below par’; with fewer pieces of the puzzle than required. Be mindful of the balance in your design, though! Story-puzzles that are too easy to solve will cause dissatisfaction in your players, whereas story-puzzles that are too hard become frustrating… which will probably lead to the player’s rejection, which in turn could cause a player to ignore your story(-puzzle) altogether.

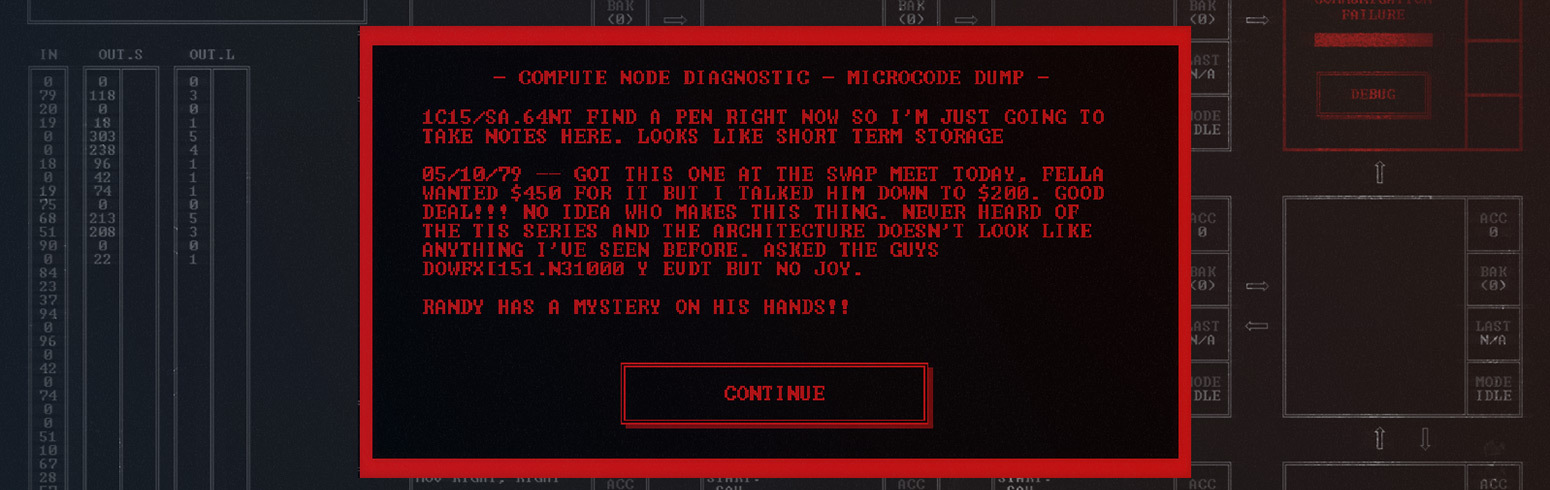

Notable examples:

- FEZ (Polytron Corporation, 2012)

- Her Story (Sam Barlow, 2015)

- Dark Souls (FromSoftware, 2011)

- Five Nights at Freddy’s (Scott Cawthon, 2014)

- TIS-100 (Zachtronics, 2015)

- The Swapper (Facepalm Games, 2013)

- The Talos Principle (Croteam, 2014)

- The Vanishing of Ethan Carter (The Astronauts, 2014)

Emergent narratives are discussed in greater detail in this other article, but to summarise: the player is left to his own devices to construct a personal story out of raw events and objects/environments. Sometimes this means that the game is randomly/procedurally generated, and all of the player’s experiences contribute to the player’s personal and unique story. In another case, the game is inconclusive about the game’s story, but allow for the player to create their own interpretation from the designs of the levels, characters and/or in-game objects.

These narratives might also be partially designed, with certain fixed elements in place. The player will still have plenty of room and opportunity to play around with the random elements in the game, to be able to construct their personal, individual experience.

Notable examples:

- Banished (Shining Rock Software, 2014)

- Civilization series (MicroProse/Fireaxis Games, 1991 and onwards)

- Crusader Kings series (Paradox, 2004 and onwards)

- Darkest Dungeon (Red Hook Studio’s, 2016)

- Minecraft (Mojang, 2011)

- Mount & Blade: Warband (TaleWorlds Entertainment, 2010)

- State of Decay (Undead Labs, 2013)

- XCOM series (Fireaxis Games, 2012 and onwards)

In conclusion

Once you figured out what the function of your story should have, you can think about the form of your story. By form I mean the way you implement the story in your game. Examples are cinematics, texts, dialogue, item descriptions, environmental design, story decision, and so on. I think that most developers jump ahead to the form too quickly (cinematics, item descriptions, etc), without putting enough thought into the function of the story. But it all starts with the function.

Think about the purpose that your story serves, and the pairing of story and gameplay may become more than just the sum of them both.

Image sources

- Angry Birds: http://www.kotaku.com.au/2012/03/why-you-should-play-angry-birds-space-the-game-everyones-talking-about/

- Assassin’s Creed 2: http://www.assassinscreed1092.com/forum/index.php?topic=659.0

- Banished: http://news.softpedia.com/news/Banished-Is-Now-Out-a-Harsher-City-Building-Strategy-Game-427852.shtml

- Batman: Arkham Asylum: https://arthouseanime.wordpress.com/2014/09/02/the-5th-anniversary-of-batman-arkham-asylum-the-video-game/

- Candy Crush: http://candycrush.wikia.com/wiki/Candy_Town

- Civilization V: http://nerdsworthacademy.com/2010/09/30/civilization-5-why-must-you-suck-away-my-life/

- Crusader Kings 2: https://www.paradoxplaza.com/crusader-kings-ii-way-of-life?___store=eu

- Dark Souls: http://steamcommunity.com/sharedfiles/filedetails/?id=121136547

- Deus Ex: Human Revolution: http://www.hardcoregaming101.net/deusex/deusex3.htm

- FEZ: https://www.smokingonabike.com/2015/03/25/fez-mysteries/

- Five nights at Freddy’s: http://freddy-fazbears-pizza.wikia.com/wiki/Plot?file=Missing_children_poster_clean.png#The_Bite_of_.2787

- Half-life: http://www.gamepressure.com/download.asp?ID=51023

- Her Story: http://gameguideworld.net/her-story-review/

- Super Mario Bros: https://gaygeekgab.com/2015/08/24/glorious-girls-of-gaming-princess-peach-aka-princess-toadstool/

- Mount & Blade: Warband: http://www.psu.com/review/31169/Mount-and-Blade–Warband-Review—PS4

- Papers, Please: http://www.technobuffalo.com/tag/papers-please/

- Plants vs Zombies: http://www.popcap.com/plants-vs-zombies-1

- Spec Ops: The Line: http://www.mattpayne.com

- TIS-100 (Banner image): https://www.gog.com/news/release_tis100

- That Dragon, Cancer: http://www.thatdragoncancer.com/#home

- The Flock: http://www.vogelsap.com/theflock/

- The Walking Dead: http://itsemmyyy.blogspot.nl/2015/07/the-walking-dead-game.html

- Valiant Hearts: The Great War: https://www.ubisoft.com/en-GB/game/valiant-hearts/

- Winter: http://www.flega.be/?p=3436

- Wolfenstein 3D: http://store.steampowered.com/app/2270/

- XCOM: Enemy Unknown: https://lutris.net/games/xcom-enemy-unknown/